The fascinating history of Craighead Caverns provides plenty of spice for tour guides as they lead groups on the hike through the immense rooms leading to the Lost Sea in the deepest reaches of the cave.

The caverns have been known and used since the days of the Cherokee Indians. From the tiny natural opening on the side of the mountain, the cave expands into a series of huge rooms. Nearly a mile from the entrance, in a room now known as “The Council Room,” a wide range of Indian artifacts including pottery, arrowheads, weapons, and jewelry have been found, testifying to the use of the cave by the Cherokees.

One of the cave’s earliest visitors was a giant Pleistocene jaguar whose tracks have been found deep inside the cave. Some 20,000 years ago the animal apparently lost his way in the darkness and wandered for days before plunging into a crevice far from the daylight he sought. Some of the bones, discovered in 1939, are now on display in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Others, along with plaster casts of the tracks, are among the exhibits at the visitor center of the Lost Sea.

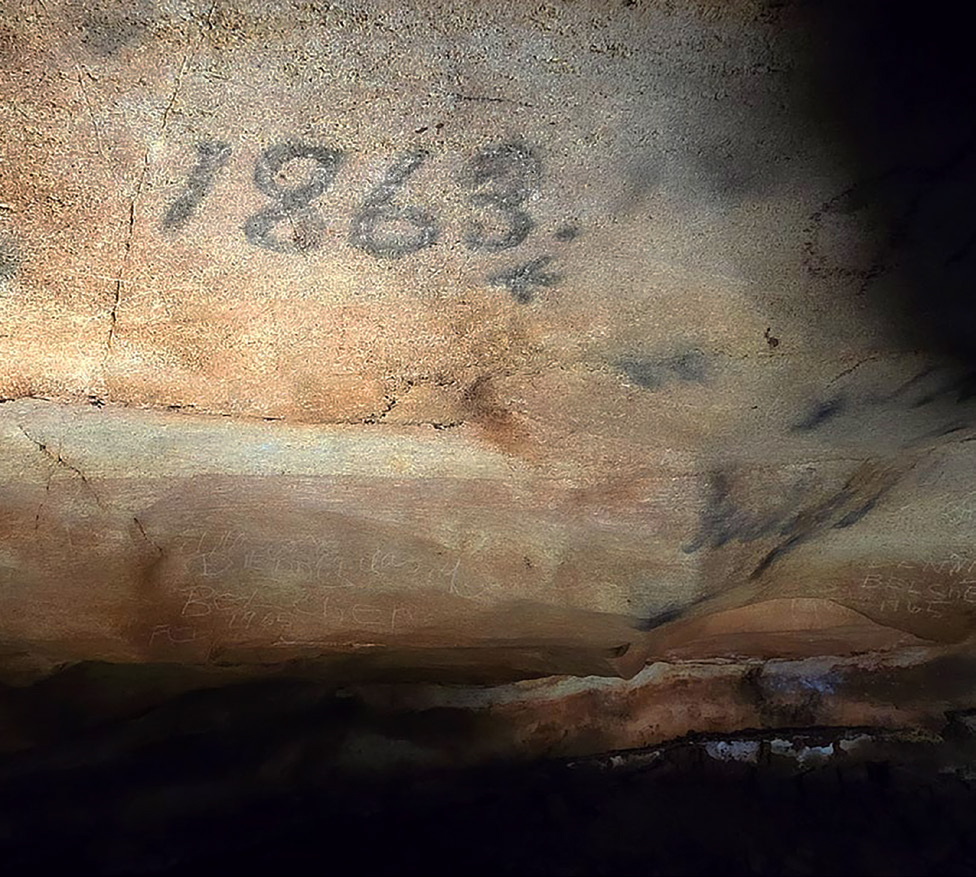

During the 1800’s, when the first white settlers arrived in the Tennessee Valley, around 1820, they also discovered the cave and used it for storing potatoes and other vegetables. The constant 58° temperature provided an ideal refrigeration system for food. Some 1863 graffitti has been carbon tested and proven to be authentic. The date was probably put there from the carbon of a confederate soldier’s torch. This is the oldest known date in the cave.

During the Civil War the Confederate Army mined the cave for saltpeter, a commodity necessary to the manufacture of gunpowder. A diary of the period reveals the intriguing story of a Union spy who penetrated the guarded cave and nearly succeeded in blowing up the mining operation before he was captured. He was, according to the diary, shot near the large gum tree at the cave entrance.

Throughout the early history there were consistent rumors of a large underground lake somewhere deep within the cave, but it was not actually discovered until 1905. In that year a 13-year-old boy named Ben Sands wiggled through the tiny, muddy opening 300 feet underground and found himself in a huge room half filled with water. The room was so large that his light was swallowed up by the darkness long before reaching the far wall or the ceiling. For the rest of his life Sands delighted in describing how he threw mudballs as far as he could into the blackness and heard nothing but splashes in every direction.

In 1915 the idea of developing the cave for the public was conceived. A dance floor was installed in one of the large upper rooms. Cockfights were another frequent activity in the cave. Meanwhile, other portions of the vast system were being utilized by moonshiners to produce that famous brew for which the mountains are famous.